Hello, everyone. I’m Handa from Noosology Research Institute at Musashino Gakuin University. In the past two videos, I gave a brief overview of the concept of “Noosology” since the Institute had just started.

I have talked about nature, called physis in ancient Greece, Heidegger’s attempt to recapture it with his philosophy of ontology, and Plato’s theory of ideas, among many other topics. Mostly, I wanted to convey that Noosology is a system of thought that connects physics and philosophy from an ontological perspective through quantum theory, which is the cutting edge of modern science. In a word, the fundamental objective of Noosology is the concrete establishment of what can be called an ‘existential quantum theory.’

As we are delving into these contents, I would like to start by discussing the two basic ways of what we usually refer to as ‘space.’ The premise of this discussion is related largely to what is called the “cognition problem” in philosophy. The cognition problem is the question of whether it is possible for subjectivity and objectivity to coincide.

In the 20th century, with the emergence of Husserl’s phenomenology and other works, we have made great progress on this issue. Still, we have yet to see a complete solution in philosophy. It is no exaggeration to say that most philosophy since the modern era has been centered on this issue of cognition.

So much so the issue has become very troublesome for philosophy. As I mentioned earlier, Noosology aims to integrate realism and idealism as an ontology for the new era of the 21st century. So it is naturally involved in this cognition problem profoundly as well. In other words, rather than raising the question of whether it is possible for subjectivity and objectivity to coincide, the focal point of Noosology is to actively search for a new way of spatial perception that will enable the coincidence of subjectivity and objectivity.

That is to unite ‘who is seeing’ and ‘what is being seen.’ — It means to create an entirely new way of world cognition. First, for everyone to understand this correctly, it is necessary to define our subjectivity and objectivity from a spatial perspective. In this video, I would like to start talking about it under the title, “The ontological differences hidden between subjective and objective space.” It is a bit difficult, but I hope you understand. Let’s get started.

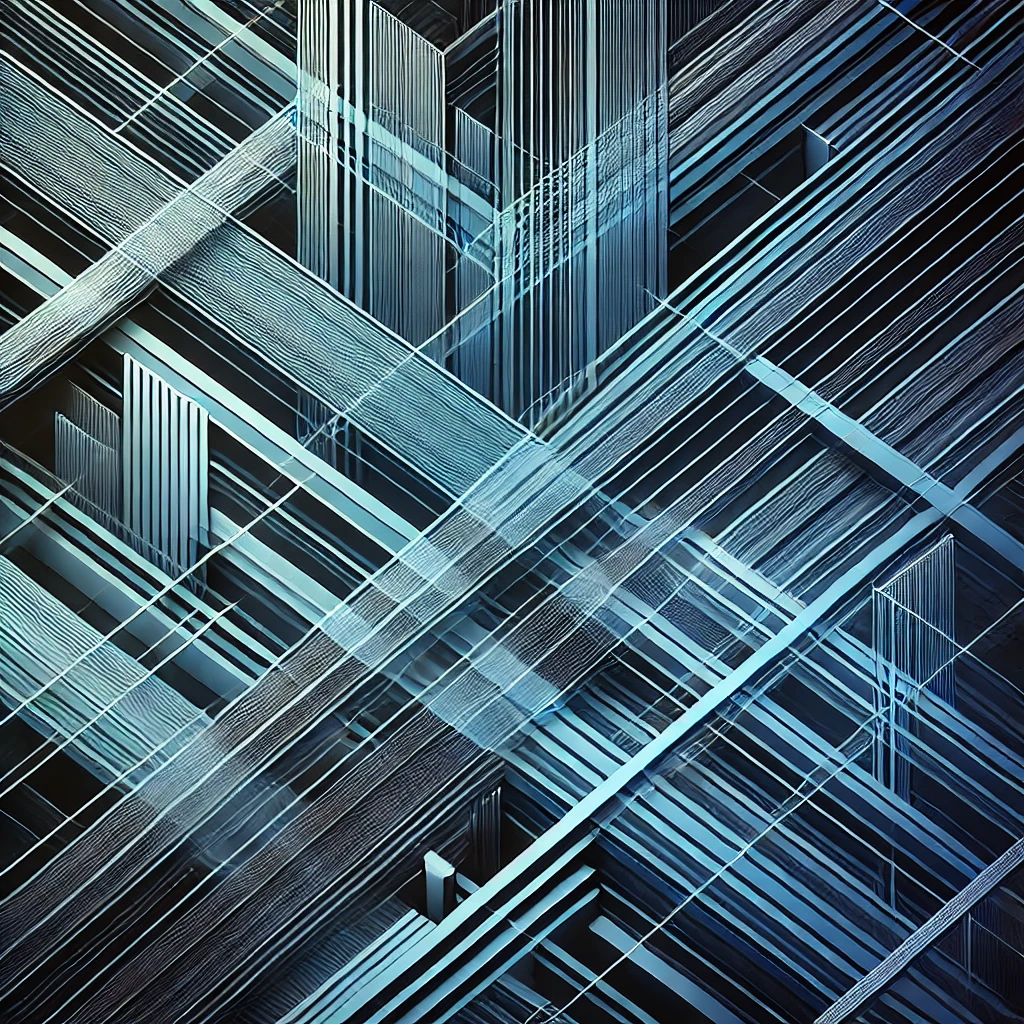

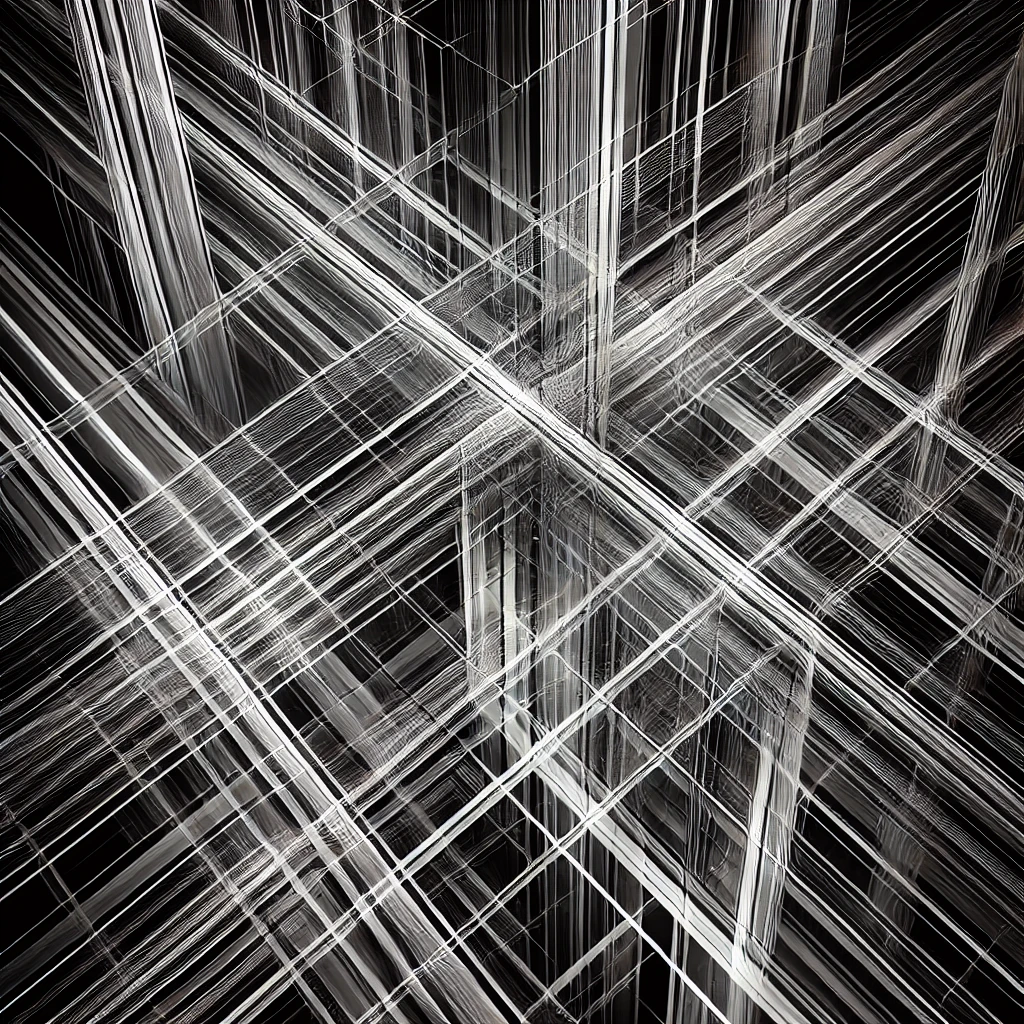

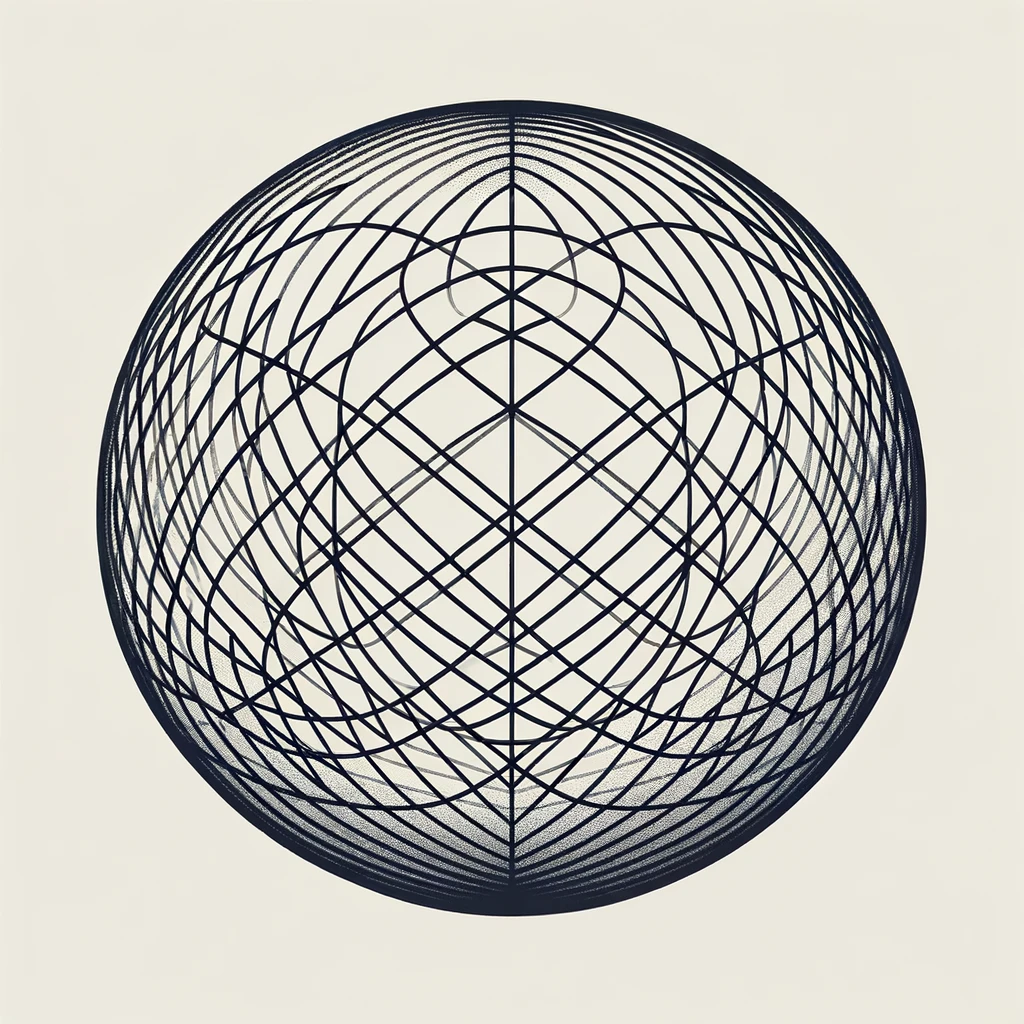

First, please take a look at these two figures.

These figures illustrate the two spaces we imagine in our awareness of our existence. They are the basics of the two spaces in our experience of consciousness. If you take the time to look at them, you will immediately see the implications. Let’s take a closer look at the left one.

As you can see, this figure shows the space when you think you exist in a space surrounded by an external space. In short, it is an external space. Here, space is perceived as an expanse with a vast extension, and you are a material being located within it. In other words, “I,” the self, is grasped as a physical body. In this case, “I,” as an individual body, must be imagined as a parallel entity in space with other objects, such as an apple. This is the image of what we call objective space.

On the other hand, the space represented on the right is the space that “I” actually perceive. In the objective space on the left, the relationship between “my body” and the apple, which was imagined as parallel, is expressed as a relationship between ‘what visualizes’ and ‘what is visible’ in the figure on the right.

As can be easily seen from the figure, unlike the space on the left, there is no head or face in this space. In particular, as for eyes, since it is impossible in principle to see one’s own eyes, the eyes can never be the object of vision in this space. In this sense, if the space on the left side is called the objective space, the space on the right side can be called the subjective space. It is clear that these two spaces must be considered separately.

In game terms, it corresponds to the relationship between TPV and FPV, between third-person and first-person perspective spaces. From the above, we can say that the objective space is from the third-person perspective, so it is not the space that “I” am actually seeing. Thus, the objective space is invisible. This space is the space from which “I” am seen from the outside of “my body,” so to speak, and we usually call such a space the external space. On the other hand, the figure on the right side shows the space where “I” am living as a living body (life-world), and as I mentioned earlier, this space is the space working as ‘what visualizes.’

If the left figure depicts an external space in which you see yourself from the outside, the right one is, in a sense, an internal space that you see from the inside of yourself. A French philosopher, Gilles Deleuze, has greatly influenced Noosology and will be mentioned frequently in this series of research videos. He used the phrase “the eye is a screen” to emphasize the realistic nature of the eye in the subjective space depicted in the figure on the right. Interesting, isn’t it? — because the eye is usually likened to a camera, not a screen.

This is because we recognize our eye as a material object, the eyeball, in the objective space on the left. In the subjective space on the right, however, the eye is no longer an object but a very screen for ‘seeing.’ Through such a provocative expression, Deleuze was trying to say that there is a gap between objective and subjective space. Moreover, this gap is the one that cannot be overcome.

In philosophy, such a difference is called ontological difference. The term “ontological difference” will come up more often in future research videos, but for now, please understand it as the difference between ‘what exists’ and ‘to exist.’ This term originally comes from Heidegger’s philosophy.

Now, let us consider this again. As I have just described, our general cognition of space is almost oblivious to the difference between objective and subjective space. What I mean is that what science usually calls space, for example, is objective space, which in this case, is the space shown in the figure on the left. You see what I mean. From this perspective, my physical body exists in the vast expanse of space called the universe, and in front of my body, for example, is an apple. It is in this spatial image that we understand the relationship between ourselves and the world. Therefore, if we recognize space within this conceptual framework, we will naturally end up with physical explanations of the perceptual experience of seeing, as described in ordinary textbooks.

That is, visible light strikes the surface of the apple, where the apple reflects only light that falls in the red frequency range. The reflected light enters the eye, the stimulus reaches the visual center of the brain through the optic nerve, and the electrical firing of synapses (note: junctions between neurons, which are nerve cells that make up the brain) causes the image of a red apple to form in my brain: Today, this is common knowledge that our consciousness is born in the brain.

However, this leads to a vicious cycle: who is looking at the image of the apple in the brain, and is there a small dwarf in the brain? The cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett has sarcastically called this sense of consciousness in modern neuroscience the Cartesian Theater. By “Cartesian theater,” he meant the theater of Descartes’ followers because neuroscientists, in the arrangement shown in the figure on the left, still think about ‘seeing’ in terms of the subject-object dualism that has existed since Descartes. Dennett says that we should immediately discard the assumption that we can find a subject, a conscious “I,” in a particular neuron in the brain.

Well, the idea itself must be fundamentally wrong, don’t you think? In fact, how can the working of the brain, which is merely a collection of electrical chemical reactions, produce the subjective experience of consciousness that is expressed in the space on the right? In other words, how can the brain as a mere substance produce the experience of the redness of an apple or the sweet and sour aroma of an apple?

These sensory textures of sight, smell, etc., are now called qualia in neuroscience. There is no way to measure these qualia from external physical processes anymore. Neuroscientists call this problem the brain’s “hard problem,” and some even say that science will never be able to solve it.

And this problem is, of course, deeply connected to the philosophical problem. As you can see, the space represented in the figure on the right is the space in which “I,” the irreplaceable consciousness that cannot be exchanged with anyone else, or in other words, the space where existence is alive. Existence, in Heidegger’s sense, means “ecstasy (ekstase): outside one’s own self.” It means to be out of your ‘real existence.’ — It provokes an image of the soul. Isn’t it interesting?

In philosophy, we usually call the world of space, like the left figure, ‘real existence.’ This corresponds to space-time in the physical sense, so it is ‘real.’ However, the space we actually perceive is not space-time. This is clearly shown in the figure on the right. Do you understand? It might be confusing at first, though.

Precisely, the “being” and “existing” in existence are reworded as “existent” and “real,” and their difference is expressed in the spaces on the right and left sides of this figure. In fact, there was a Japanese philosopher who intuitively realized this. His name is Shozo Omori. He was a professor at the University

of Tokyo. Omori expressed the difference between the two spaces quite simply with the term “face-body bifurcation.” It means branching of the “face” and the “body.” From Noosology’s viewpoint, his expression is somewhat crude but very concise at the same time. Omori would say that the space on the right is the “face,” and the left is the “body.” Omori’s “face” refers to the perceptual space, “what visualizes,” while “body” refers to the space of things, “what is seen.”

In these figures, the left side is the space where ‘I think’ that I am seeing the three-dimensional object, the apple. On the right side is the space where the apple is ‘actually’ seen by me. Using Omori’s expression, “face-body bifurcation,” it implies that although a three-dimensional “body” is assumed in the space of things, the actual space we perceive at the site is only a two-dimensional “face.”

What Omori was trying to express through “face-body bifurcation” is the principle that our perceptual experience is based on the branching of these two states in space. Furthermore, Omori considered that this “face-body bifurcation” was the prototype for the oppositional concepts of subjectivity and objectivity.

In other words, Omori thought that the space we see is, ‘actually,’ not the “outer world” but the “inner world,” i.e., the world within our mind. This is a fascinating point. As I mentioned earlier, while science sees consciousness in the physico-chemical reactions in the brain, the philosopher Omori regarded the space in front of him, his perceptual front, as a space completely separated from the “outer world.” He considered it to be his “inner world” in its own right.

The world we perceive is our “internal world” as it is, as it appears. — How does it sound to you? Do you understand the core of his concept? We usually think of the world we see as the “outside world,” but Omori says, no, that’s not true. It is not “outside” but “inside.” I would be applauding him, shouting a big “Yes!” Omori’s concept of the “face-body bifurcation” is regarded as” Non-brain concept”, a criticism against the excessive bias of modern science, which emphasizes only the brain in the origin of human consciousness. Noosology is also a more modern takeover of Omori’s” Non-brain concept”, in the sense that the basis of consciousness does not exist in the brain.

Now, let’s wrap up today’s talk. The space, which we consider a single vast expanse, hides a secret division into objective and subjective. Nevertheless, we do not yet have a concept that clearly separates the differences between these two spaces.

As the brain science example I mentioned earlier illustrates, we have identified the subjective space within the real material space. Then we are trying our best to find the place where consciousness works within it. This identification, or rather to call it confusion, must first be confirmed. The relationship between where our objectivity arises and where our subjectivity is born must be carefully distinguished and firmly separated with more precise geometric equality than Omori’s “face-body bifurcation” concept.

For the sake of our minds, which have lost their way under today’s one-sided discourse of the scientific worldview based on the evidence-and-data-first principle, we must find a space completely different from space-time, where we can live our own existential life.

Today’s talk has been a bit long. I would like to conclude my presentation by introducing a painting. It is a work by the Belgian artist René Magritte. He titled it The Human Condition. Please take a good look at it while contemplating the contents of this presentation. I will see you next time. Thank you for watching.