Hello, everyone. I’m Handa from Noosology Research Institute at Musashino Gakuin University. I have been able to get into what seems to be the explanation of Noosology since the last video. In the video, I briefly explained the difference between objective and subjective space by using the term “ontological difference” to distinguish those spaces.

Noosology starts by transforming the concept of ontological difference into clear geometric images and incorporating it into our spatial cognition. Through this new spatial cognition, Noosology introduces a system of thought that opens up what Heidegger called “being,” which is submerged in our unconscious.

Today, I will discuss Shigeki Noya’s “view theory” in order to help you better understand the nuances of the ontological difference between objective and subjective space. By contrasting with Noya’s “view theory,” you can comprehend the new spatial cognition that Noosology attempts to open up.

So, the title of today’s video will be “Can we ever have a view in ‘view theory’?” — sounds very challenging, doesn’t it?

Now, let’s get started. First, I would like to introduce Mr. Shigeki Noya briefly.

Shigeki Noya is a student of Shozo Omori, whom I introduced previously. Noya is now considered one of Japan’s leading philosophers. In short, Noya’s philosophy tries to dismantle the conventional philosophical perspective that emphasizes subjectivity.

I will repeat; He tries to dismantle the conventional philosophical perspective that emphasizes subjectivity. Those who are familiar with philosophy may already know that Western philosophy since the modern era, since Kant, has developed measures that emphasize subjectivity. In the pre-Kantian period, the common notion was that there was first an objective world of objects, from which the subjective world of consciousness emerged in each individual human being. Kant’s famous Copernican Turn in epistemology, in which “perception does not follow the object, but the object follows perception,” led to the idea that the world is shaped and exists according to human cognitive capacities.

In fact, Husserl, the modern successor of Kant, developed phenomenology with his lifelong theme of how the objective world is shaped and constituted in human consciousness from the subjective world.

In phenomenology, the world, which had been conventionally considered objective, was interpreted as being created by the cooperative relationship between different subjectivities and thus was called intersubjectivity. Husserl’s phenomenology later became one of the significant trends in contemporary philosophy. However, whether Husserl succeeded in constructing an intersubjective world in which one’s subjectivity and the subjectivity of others exist harmoniously on an equal footing is questionable. Some say that phenomenology is not exempt from solipsism, and there is still no clear answer to this question yet.

From early on, Noya may have felt the limitations of a philosophy that takes subjectivity as its starting point. In a recent interview, Noya stated that the idea of his philosophy was how to deny the subjectivity of cognition, which had been the premise of philosophy. In other words, he searches for a new possibility of a new philosophy based on the denial of subjectivity.

Well, it’s interesting. Noya says such an assumption as subjectivity in cognition is like one’s consciousness being locked up in his/her front.

The characteristic of Noya’s philosophy is that it extracts and rescues one’s consciousness from his/her front. It transfers the field of his/her conscious experience into reality, i.e., real existence. In other words, it attempts to extract the subject of “I” at the level of action rather than cognition. In a sense, Noya’s thought is a novel approach to solving the cognitive problem of whether subjectivity and objectivity can coincide, as discussed previously, within the context of naive realism, the image of the world as we usually think of.

Simply put, there is no such thing as a separation of subjectivity and objectivity; only the external world exists. In developing this new theory of realism, Noya uses a two-tiered structure, “view theory” and “aspect theory.”

He wonders if it is possible to achieve a unity of subjective-objective worldview within our ordinary sense of existence, called “the natural attitude” in philosophy. This is an exciting approach. In his theoretical development, the “view theory” is directly related to Noosology.

The “view” refers to the view of the world. As for the other one, the “aspect theory” is a bit more complicated, so I would like to introduce the “view theory” and discuss the problem with Noya’s theory from the perspective of Noosology.

First, let’s pick up the key points of the “view theory” from his book, “The Conundrum of the Mind”. I will read it: “For example, suppose I am standing by the window of a college classroom and say, “I can see the SKYTREE from here.”

Who would have thought it was a report of my state of consciousness? Another person beside me heard my comment and said, “It’s true. I can see the SKYTREE from here.” Then, why should I call the fact that I can see the SKYTREE from my classroom window subjective?

If we follow our sensations in daily life, isn’t the fact that we can see the SKYTREE from that window an objective matter about the way the world is? “

Well, it goes like this. What do you think? Noya, a disciple of Shozo Omori, is well known as a philosopher who uses easy expressions that anyone can understand. Here, too, we can see that he describes his precise philosophical position in straightforward and simple language.

In other words, according to Noya’s view theory, a view itself is “real” in nature. Moreover, to use Omori’s expression introduced in the last video, “seeing something,” no matter what it is, is merely the experience of one phase, i.e., “a face,” in the “face-body bifurcation.”

What he means by the “view” is that a part of the totality, the “body,” is seen as the “face.” So, what he says is what it is. Philosophy usually considers that the world grasped as a “face” is a product of consciousness generated by the organs of perception. In contrast, Noya proposes the concept of a “view,” which is not the way one experiences the world but the way the world is grasped from a certain viewpoint in space in a certain condition.

In other words, he is trying to move the base of the phenomenon from the realm of “I,” the subjectivity, to the real, the objective world.

This means the negation of personhood in seeing. Do you understand? In other words, there is only a difference between “here” and “there” in terms of the position of the viewpoint in space, and we must not place “I” or “you” in “here” or “there” in terms of the personification of the viewpoint. According to his theory, there is no personhood in a point of view.

Therefore, if I stand where others stand, I will see the same view they see, and conversely, if others stand where I stand, they will have the same external perception as I do. Noya assumes such a spatial image.

Thus, Noya’s view theory aims to unify human visual perception in a manner to fit each individual’s subjective space, which we usually assume is personal, into real space as a piece of objective space like patchwork.

Noya probably got the idea for this concept from his teacher Shozo Omori’s idea of the “face-body bifurcation.” However, in a sense, Noya’s idea directly opposes Omori’s. What I mean is that, as I mentioned previously, Omori identified the mind of the viewer with the perceptual landscape itself as a “face” of the “face-body bifurcation.”

On the other hand, as you see, in Noya’s view theory, one’s perceptual landscape is merely a part of the external objective world, so there is no room for an individual mind, i.e., one’s subjectivity, to appear. For Noya, what Omori regards the mind is developed in the following logical framework, the “aspect theory.”

The view theory is based on the spatial range of the viewed object and the viewer’s location, while the aspect theory adds the passage of time to the spatial range. When time is added, naturally, the free-acting viewpoints of the viewer thus create a continuity of different perceptual landscapes that becomes a unique narrative associated with those landscapes.

What emerges from this context is, what Noya calls, an “acting subject.” For him, the concept of a subject is not a subject of perception but that of action. Furthermore, in the specificity of this acting subject, in its unique individuality, the distinction of personhood such as “I” or “you” arises.

In physics terms, this means that Noya sees the origin of personhood in the world line, which refers to the locus of the motion of a mass point in 4-dimensional spacetime. By thinking that way, he believes that the distinction between subjectivity and objectivity is no more problematic than conventional philosophy considers and that everything can be consistently described within the spacetime of the real world.

Of course, there are many other detailed arguments, but the above are the main points Noya makes through the view and aspect theories. Well, it is a fascinating approach. However, from Noosology’s point of view, his approach seems to have a big pitfall.

In my opinion, it is necessary to think more in depth about the significance of the “face” in Omori’s concept of “face-body bifurcation” to determine the pros and cons of Noya’s view theory. Again, what Noya calls a “view” is a field of vision.

It

corresponds to a “face” in Omori’s “face-body bifurcation.” As I mentioned, it is “what is seen,” that is to say, a “face” of objective space viewed from a certain direction. So simply put, we can say that it is a 2-dimensional space corresponding to a cross-section or a projective surface of a 3-dimensional space.

In fact, Noya also interprets his “view” as such. However, on the other hand, the “face” that Omori refers to in the “face-body bifurcation” is a perceptual front. In other words, to Omori, it is one’s personal visual space. At this point, we can see the difference between their notions, which is the problem.

Is the “face” interpreted as a cross-section of objective space the same as the “face” as one’s perceptual front, which is one’s personal visual space? From Noosology’s perspective, I feel that Noya is largely missing the point of what Omori considers one’s perceptual front: Omori regards the perceptual front as the very place where phenomena appear.

For Omori, perceiving means that one always puts his/her thought into what he/she perceives. He even goes so far as to say, “There is no such thing as perception without thought. If I can see things, then everything I see in the world must be the image of my mind.”

The mind is, for Omori, not an enigma hidden inside us but something that extends to the ocean, the sky, the sun, the moon, and the world of the stars. Here is what Omori means when he refers to the perceptual front as the “mind.”

When I consider the face of the “face-body bifurcation” in this context, I understand that it includes the entire world of 3-dimensional space. In other words, the face cannot be a simple 2-dimensional surface. If this is the case, where is the position of the person who sees this entire 3-dimensional space as a plane, i.e., the “face”?

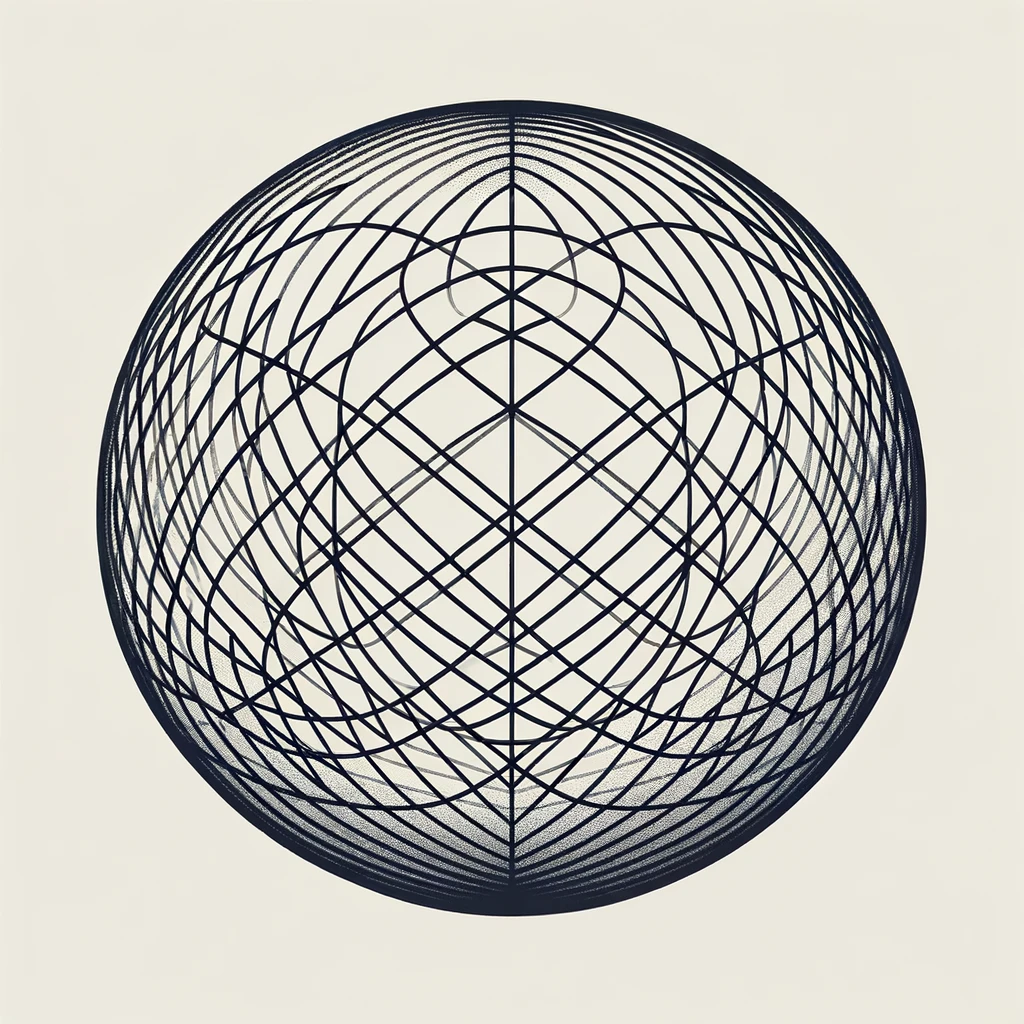

The line of sight, in this case, should be orthogonal to the 3-dimensional space. Thus, it does not exist in the 3-dimensional space but in the 4-dimensional space. The figure here illustrates this. The left side shows the space where Noya’s concept of the “view” is created.

As you see, if you look at the world from a position in three dimensions, the world you see is 2-dimensional. In this sense, this plane is a cross-section of 3-dimensional space. On the other hand, the image on the right indicates a plane, Omori’s “face,” as the perceptual front, where the 3-dimensional space is seen as a plane. Here, the three straight lines drawn on the “face” represent the 3-D coordinate axis X, Y, and Z.

The difference is obvious, isn’t it? While Noya places one’s viewpoint in a 3-dimensional space, Omori’s viewpoint in his theory of perceptual front does not exist in the 3rd dimension but protrudes into the 4th dimension. To use Deleuze’s analogy, Noya still thinks of the eyes as a camera’s position, whereas Omori, perhaps like Deleuze, regards human eyes as a screen.

“The subject does not belong to the world, but it is a limit of the world.” — This is Wittgenstein’s famous saying. The essence of Omori’s theory of the perceptual front is that, just like Wittgenstein’s words, the position from which we see the world does not exist in 3-dimensional space. If this is the case, Noya’s idea that the “view” is identified by the relationship between the spatial position of an object and a viewer’s location must be complete fiction.

In other words, even if I change my position in 3-dimensional space from “here” where I am standing to “there” where you are standing, I cannot see the world as you perceive it, and it remains my own world.

Therefore, Noya missed grasping the 4-dimensional actuality of seeing. It is not possible to have a “view” in his “view theory.” In 3-dimensional space, there is no such thing as a viewpoint, whether of the self or of others.

Now, there is an artist who intuitively recognized this. It is René Magritte. In the last video, I introduced his work, “The Human Condition”, painted in 1933. In 1937, Magritte published another work titled “Not to Be Reproduced.”

This is the work. Please take a good look at it. In the composition of this picture, the person looking into the mirror on the wall has directly entered the space inside the mirror. That is to say, the person outside the mirror is copying himself into the space inside the mirror.

By giving such a title as “Not to Be Reproduced” to this work, he tried to tell the audience, “Don’t do it.” Well, what does “not to be reproduced” mean? You may have already guessed it. Think of the mirror as a “face,” a plane of the person’s visual space that creates his perceptual front.

The world in the mirror is a 3-dimensional world within his visual space. Since other beings exist in the 3-dimensional world as physical bodies, he, the subject, assumes that he is just the same existence as the others and casts himself into the mirror space as a physical image.

In this way, he, the subject, comes to have an illusion that the position from which he is looking at the world is in a 3-dimensional space. The moment when he dips himself into the mirror space, his eyes as a screen, as before, suddenly transform into the eyes of a camera. In my opinion, Magritte named the work “No to Be Reproduced” to warn us not to do such a thing.

It means that the world opens up before your eyes. In other words, a view is only possible when one’s gaze emerges from outside the mirror. The subject is never inside the mirror. Please remember what I discussed previously about the “ontological difference.”

The ontological difference between subjective and objective space is, precisely, the difference between the outside and inside of the mirror that Magritte depicted in his work. We must now clearly bring this difference to our awareness. By doing so, we can open the door to a new higher dimension of perception, although which has been right here in front of our eyes for a long time, we have never been able to notice before.

That is the horizon of the ontological space that Noosology predicts humans will be moving into in the future. So, that’s all for today. See you next time.